Entrevista a Emily Casanova: teoría neandertal del autismo

A raíz de la newsletter sobre el posible origen neandertal del autismo, me decidí a entrevistar a su investigadora principal, la dra. Emily Casanova, quien además es autista.

Le escribí un email sin mayores pretensiones y me respondió amablemente a todas mis preguntas. ¡No os lo perdáis!

Me interesó especialmente tu último artículo Enrichment of a subset of Neanderthal polymorphisms in autistic probands and siblings [Enriquecimiento de un subconjunto de polimorfismos neandertales en sujetos autistas y hermanos autistas], en el que tú y tu equipo pudisteis rastrear esos SNP de la población autista hasta los neandertales (ya que estaban muy conservados).

Sin embargo, lo que más me fascina es el concepto de "subconjunto de genes". Cada individuo autista es único, pero el procesamiento botom-up, el monotropismo y los problemas sensoriales parecen ser las características principales. Casi parece como si el conjunto de genes autistas viniera en un pack, y todos ellos trabajaran e interactuaran juntos para crear el procesamiento autista. Lo que me lleva a las siguientes preguntas:

1) ¿Qué opinas al respecto? ¿Sería posible que el legado derivado de los neandertales viniera como un pack indivisible (al menos en lo que se refiere al sistema nervioso)? ¿Cuál sería la razón genética para que eso ocurriera (lo único que se me ocurre es la proximidad cromosómica y, por tanto, una menor probabilidad de recombinación)?

Emily Casanova: ¡Esa es una muy buena pregunta! Sabemos por la genética del autismo que hay definitivamente un subconjunto de genes que están repetidamente implicados en su etiología, pero que ese subconjunto es en realidad bastante grande. Por ejemplo, hay cientos de genes llamados de "efecto mayor" que, cuando mutan, son un factor importante en la probabilidad de que se produzca el autismo.

Pero también hay miles de genes de "efecto menor" que desempeñan un papel cuantificable, pero más pequeño. En estos casos, es más probable que el autismo sea de naturaleza poligénica (multigénica), con múltiples genes que desempeñan un papel combinatorio.

Muchos de estos genes relacionados con el sistema nervioso tienden a estar muy conservados, lo que significa que apenas cambian con el tiempo. Esto contrasta con otros grupos de genes, como los metabólicos o los inmunitarios, que evolucionan mucho más rápido. Una de las principales razones por las que los genes del sistema nervioso no evolucionen más rápido es que tienden a ser lo que se conoce como "dosis-sensibles", lo que significa que no se puede variar su número de copias, hacia arriba o hacia abajo, sin causar algunos problemas importantes en el desarrollo del cerebro. Su sensibilidad a las dosis es probablemente el resultado de que a menudo están implicados en complejos de proteínas o vías realmente importantes que no pueden tolerar muchos cambios.

Así, cuando un solo gen de estos complejos/vías muta, presiona a otros genes de la red para que también cambien. Se acaba viendo un patrón en el que estos genes no cambian mucho durante mucho tiempo, pero de repente, cuando se produce el cambio, se pueden ver regiones aceleradas de cambio evolutivo.

¿Qué tiene esto que ver con nosotros, los neandertales y la hibridación? Aunque los neandertales son nuestros parientes más cercanos ―ahora extintos―, tras la separación inicial de nuestros linajes se produjeron algunos cambios en la evolución de los genes del sistema nervioso. Cuando volvimos a juntarnos, esta diferenciación pudo provocar desajustes en estas redes de genes.

Por poner un ejemplo hipotético, las dosis de genes A, B y C pueden funcionar bien en Homo sapiens y neandertales, respectivamente, pero cuando, digamos, se pone un A neandertal con un B y un C de H. sapiens, de repente, ese desajuste podría causar ciertos problemas.

El otro aspecto interesante, el que me llevó a adentrarme en este campo de investigación, pero que de momento es muy especulativo, es si el desajuste entre las distintas versiones de los genes durante la hibridación puede causar algunos problemas. Pero, por otro lado, también sospecho que podría ser un arma de doble filo y proporcionar algunas ventajas, como efectos sobre la inteligencia o la creatividad. Esta posibilidad es la que más me intriga y emociona.

Según la literatura sobre hibridación, la mezcla entre especies estrechamente emparentadas puede ser a menudo un estímulo para nuevos cambios en las siguientes generaciones de descendientes. Es un acontecimiento que desestabiliza el genoma, y con ello pueden surgir cosas no tan buenas (por ejemplo, en el caso del autismo, problemas sensoriales, depresión, ansiedad, problemas de comunicación, trastornos hormonales, síndrome de Ehlers-Danlos, etc.), mientras que, por otro lado, la mejora de habilidades como el arte, la mecánica, el aumento de la memoria semántica (no contextual, por ejemplo, el aprendizaje de libros) pueden proporcionar algún beneficio adaptativo y social.

Basándome en mis estudios, sospecho que la mayor parte de lo que estamos viendo en nuestros genomas humanos modernos es un desajuste leve, que puede conferir tanto ventajas como desventajas. Pero, como ya he dicho, se trata de especulaciones, así que hay que tomarlas con cautela.

2) Tu trabajo también se centra en los trastornos del tejido conectivo, como el Ehlers-Danlos y su solapamiento con el autismo. ¿Crees que también podría formar parte de ese reducto de ADN neandertal?

E: Tengo muchas ganas de explorar esa posibilidad. Pero, por desgracia, parece que vamos a tener que esperar a que se publiquen los resultados del estudio HEDGE y (con suerte) los datos genómicos se pongan a disposición del resto del mundo científico para su estudio. Este proyecto ha recogido más de 1.000 genomas de personas con síndrome de Ehlers-Danlos hipermóvil (hEDS) y el equipo calcula que publicará sus primeros resultados en 2025. Así que cruzo los dedos para que los datos se pongan a disposición de otros científicos, de forma muy similar a la base de datos SPARK para el autismo.

3) ¿Te importaría compartir algunas ideas sobre el fenotipo ampliado?

E: Sospecho que el ADN neandertal también puede desempeñar un papel en el fenotipo ampliado autista. Definitivamente vimos algunos indicios de que los hermanos no autistas compartían algunas de las mismas tendencias que vimos en el grupo autista.

Sin embargo, en futuras iteraciones de nuestro estudio necesitaremos un mayor número de participantes para abordar este tema con mayor profundidad, algo en lo que estamos trabajando actualmente.

4) ¿Crees que sin una selección positiva, la evolución podría haber borrado por completo el ADN derivado del neandertal en los humanos modernos? ¿O al menos dejarlo cercano al 0%?

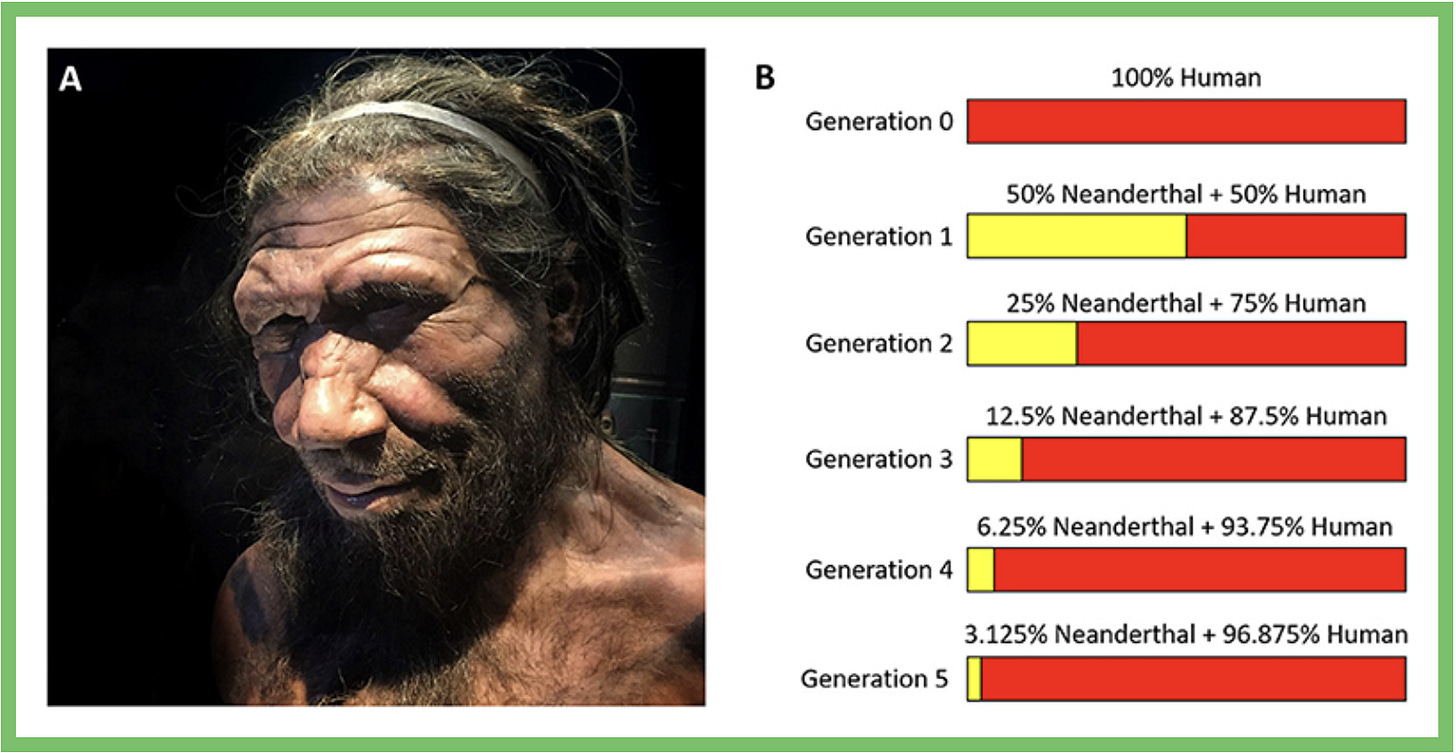

E: El ADN neandertal se ha ido eliminando lentamente del genoma de H. sapiens con el paso del tiempo. Hace unos 30.000 años, había entre un 5 y un 6% de ADN neandertal en el genoma euroasiático. Ahora, está más cerca del 1-3%.

La pérdida de ADN neandertal a lo largo del tiempo es, sin duda, en parte el resultado de la eliminación de variantes genéticas que no funcionan bien juntas y provocan algunos problemas de salud graves, como la mortalidad infantil o la infertilidad. Normalmente, esto sucede con bastante rapidez, de forma que estas variantes "realmente malas" probablemente se eliminaron del genoma del H. sapiens, digamos en 100 generaciones, si no antes.

Sin embargo, la pérdida de parte de este material genético también es un resultado natural de la genética de poblaciones y de los grandes números. Cuanto más grande es una población reproductora, más rápido se eliminan estas variantes menores con el tiempo, sin otra razón que la de no ser tan comunes.

Por lo tanto, parte de esa pérdida del 5-6% al 1-3% [del ADN neandertal] es sólo por la naturaleza de la probabilidad. La probabilidad favorece lo común.

Por lo tanto, se puede ir un paso más allá y suponer que, con el tiempo, el porcentaje de neandertales seguirá disminuyendo, excepto en el caso de las variantes que se han vuelto realmente útiles y están presentes en una parte suficientemente grande de la población.

5) Curiosamente, esas primeras generaciones de humanos mezclados eran "más neurodivergentes" (permíteme la inexactitud), mientras la evolución trabajaba para eliminar algunas cosas deletéreas desfavorables. Entonces, la "epidemia autista" que algunos pretenden, sería, en realidad, una neurotípica. Además, la eugenesia ha funcionado bastante bien en los últimos dos siglos. Dejando a un lado el cambio climático y algunos acontecimientos desafortunados, ¿dónde ves la evolución de la naturaleza humana en los próximos 10.000 a 100.000 años? ¿Crees que favorecerá las características autistas o estamos condenados?

E: “Mientras existan seres humanos, sospecho que siempre habrá personas autistas.”

En el caso de los tipos de autismo que se heredan y se transmiten de generación en generación, creo que esa espada de doble filo vuelve a entrar en juego. Sí, hay cosas con las que lidiamos que, en teoría, deberían eliminarse porque pueden perjudicarnos, como los problemas de fertilidad (síndrome de ovario poliquístico), los trastornos endocrinos, las enfermedades inflamatorias, la ansiedad grave, los problemas sociales que pueden afectar a nuestra capacidad para encontrar pareja y reproducirnos… la lista es interminable.

Pero el autismo es un espectro de condiciones opuestas: sí, puede ser una discapacidad, pero también hay a menudo diferentes capacidades, lo que sospecho que es parte de la razón por la que seguimos apareciendo, generación tras generación, y por qué hay tantos genes diferentes implicados en nuestra población.

El autismo relacionado con el ADN neandertal probablemente seguirá desapareciendo con el tiempo, aunque algunas variantes pueden permanecer. En definitiva, el ADN neandertal es sólo una faceta de la increíblemente complicada historia genética del autismo.

Esto es todo por hoy, muchísimas gracias a Emily Casanova por su tiempo. Si te ha gustado, no olvides suscribirte y compartirlo!

Se vienen novedades muy pronto!

Lee el artículo completo de Emily Casanova aquí.

Échale un vistazo a la preventa del nuevo libro de Alejandra Aceves sobre el (T)DAH. Código PREVENTA para un 20% de descuento.

Próximo número de la revista autista sobre las etapas vitales. ¿Cómo es crecer siendo autista? ¿Qué necesitamos al envejecer? etc, etc… muy pronto! Suscríbete en papel para que te la mandemos directamente a casa. Y en PDF son gratis, así que no tienes excusa: descárgatelas :)

Versión original de la entrevista en inglés:

I got particularly invested in your last paper about the "Enrichment of a subset of Neanderthal polymorphisms in autistic probands and siblings", where you and your team could clearly trace those SNPs from the autistic population back to the Neanderthals (as they were heavily preserved). What fascinates me, however, is the concept of a "subset of genes". Each autistic individual is unique, yet bottom-up processing, monotropism, and sensory issues seem to be the main features. It almost feels as if the autistic set of genes comes in a tight pack, and all of them work and interact together to create the autistic processing. Which leads me to the following questions:

a) What do you think about this? Would it be possible for the Neanderthal-derived legacy to come as a somewhat inseparable bundle (at least referring to the Nervous System)? Why would be the genetic reason for that to happen (all I can think about is chromosomal proximity and thus, less likelihood of recombination)?

That’s a really good question! We know from autism genetics as a whole that there’s definitely a subset of genes that are repeatedly implicated in its etiology, but that the “subset” is actually quite large. For example, there are hundreds of what are called “major effect” genes that, when they’re mutated, are a major factor in the likelihood autism will occur. But there are perhaps thousands of “minor effect” genes that play measurable but smaller roles too. In these instances, the autism is more likely to be polygenic (multigene) in nature, with multiple genes playing a combinatorial role.

A lot of these nervous system-related genes tend to be very conserved, meaning that they don’t change very much over time. This is in contrast to other gene groups, like metabolic or immune genes that evolve much faster. One of the major reasons nervous system genes don’t evolve very fast is they tend to be what’s known as “dosage sensitive,” meaning that you can’t really mess with their dosages, up or down, without causing some major problems in brain development. Their dosage sensitivity is most likely a result of the fact they’re often involved either in tight knit protein complexes or really important pathways that can’t tolerate much change. So, whenever a single gene in these complexes/pathways mutates, it puts pressure on other genes in that network to change as well. You end up seeing this pattern where these genes don’t change much for a long time, but suddenly when change does occur, you might see accelerated regions of evolutionary change.

What does this have to do with us, Neandertals, and hybridizing? Even though Neandertals are our closest now-extinct relative, there were some changes in nervous system gene evolution after our lineages initially split. When we came back together, that can sometimes lead to mismatch in these gene networks. For a hypothetical example, gene dosages of A, B, and C may work well in Homo sapiens and Neandertals, respectively, but when you, say, put a Neandertal A with a H. sapiens B and C, suddenly that mismatch might cause some problems.

The other interesting thing—one that actually got me into this area of research in the first place, but which is very speculative at the moment—is that, yes, mismatch between different versions of genes during hybridization can cause some problems. But on the other hand, I also suspect it could be a bit of a double-edged sword and provide some advantages as well, such as effects on intelligence or creativity. It’s this possibility that actually intrigues and excites me the most. From the hybridization literature, intermixing between closely related species can often be a stimulus for new changes in subsequent generations of offspring. It’s a destabilizing event in the genome and with that can come some not-so-great stuff (e.g., in autism like sensory issues with autism, depression, anxiety, communication challenges, hormone disorders, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, etc.), while on the other hand enhanced abilities like art, mechanics, increased semantic (non-contextual, e.g., book-learning) memory may provide some adaptive and societal benefit.

Based on my studies, I suspect most of what we’re seeing in our modern human genomes is mild mismatch, which may confer both advantages and disadvantages. But as I said, this is currently speculative, so it should be taken with a big grain of salt.

b) Your work also focuses on connective tissue disorders, such as Ehlers-Danlos and its overlap with autism. Do you think it could also be part of that Neanderthal DNA bundle?

I am very eager to explore that possibility. But unfortunately it seems we’re going to have to wait for the results of the HEDGE Study to be published and (hopefully) the genomic data to be made available to the rest of the scientific world for study. This project has collected over 1,000 genomes from people with Hypermobile Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome (hEDS) and the team is estimating they will publish their first results in 2025. So, I’m really keeping my fingers crossed that the data will be made available eventually to other scientists, very similar to the SPARK Database for autism.

c) Care to share some thoughts about the broader autism phenotype?

I suspect that Neandertal DNA may also be playing a role in BAP. We definitely saw some indications that non-autistic siblings shared some of the same trends that we saw in the autism group. But we need larger numbers in future iterations of our study to address that more thoroughly, which we’re currently working towards.

d) Do you think that without a positive selection, evolution might have erased Neanderthal-derived DNA altogether in modern humans? Or at least leave it close to 0%?

Neandertal DNA has definitely been slowly weeded out from the H. sapiens genome over time. As of ~30,000 years ago, we had about 5-6% of Neandertal DNA in the Eurasian genome. Now, it’s closer to 1-3%. The loss of Neandertal DNA over time is undoubtedly partly a result of weeding out genetic variants that really don’t work well together and lead to some serious health issues, like infant lethality or infertility. Typically, that happens fairly quickly and these “really bad” mismatched variants were probably weeded out of the H. sapiens genome by, say, 100 generations down the line, if not earlier.

However, loss of some of this genetic material is also just a natural result of population genetics and big numbers. The larger a breeding population, the faster these minor variants get weeded out over time for no fault of their own other than they just weren’t as common. So, some of that loss from 5-6% to 1-3% is just by nature of probability. Probability favors the common.

As such, you can take this a step farther and assume that, with enough time, our Neandertal percentage will continue to go down, except for those variants that have become really useful and are present in a large enough portion of the population.

e) Funnily enough, those first generations admixed humans were "more neurodivergent" (allow me the inaccuracy), while evolution worked towards removing some unfavorable deleterious stuff. Then, the "autistic epidemic" some claim, would be, in reality, a neurotypical one. Moreover, eugenics has worked quite fine over the last 2 centuries. Setting aside climate change, and some unfortunate and dystopic events, where do you see the evolution of human nature in the next 10000 to 100000 years? Do you think it will favor autistic characteristics, or are we doomed?

So long as humans exist, I suspect there will always be autism. For those types of autism that are inherited and travel through families, generation after generation, I think that double-edged sword comes back into play. Yes, there are things we deal with that, in theory, should be weeded out because they can impair us—like fertility issues (PCOS), EDS, inflammatory conditions, severe anxiety, social challenges that may impair our ability to find a mate and reproduce, the list goes on. But autism is a spectrum condition of opposites: yes, there can be dis-ability, but there are also often different-abilities, which I suspect is part of the reason we keep popping up, generation after generation, and why there are so many different genes involved across our population.

Autism linked with Neandertal DNA will probably continue to fade over time—although some variants may stick around. But Neandertal DNA is just one facet of the incredibly complicated genetic story of autism.

Thank you Emily!

La newletter AUTIBLOG THE NEWLETTER recoge de manera periódica un contenido distinto en RRSS y Autiblog The Magazine, sobre comunidad autista. Si este estupendo artículo te gusta, SUSCRIBETE es gratis, la recibirás semanalmente en tu correo electrónico https://bio.link/autiblog